Barbara Alysen, Western Sydney University

Well may we say, “God save the Queen” …

It must be the most replayed speech by any Australian politician. It will be on the news again this week for the 40th anniversary of the Whitlam government’s dismissal. And it can be found online in earlier anniversaries and retrospectives.

One of the speech’s less remarked-upon features is that there appears to be only a single piece of surviving film. Channel Seven cameraman Bob Wilesmith shot it, and it has since been circulated across the networks over the years.

The way in which Wilesmith’s footage has come to dominate Australians’ recollection of November 11, 1975, is a story of prescience, luck and the limitations of the TV news technology of the day.

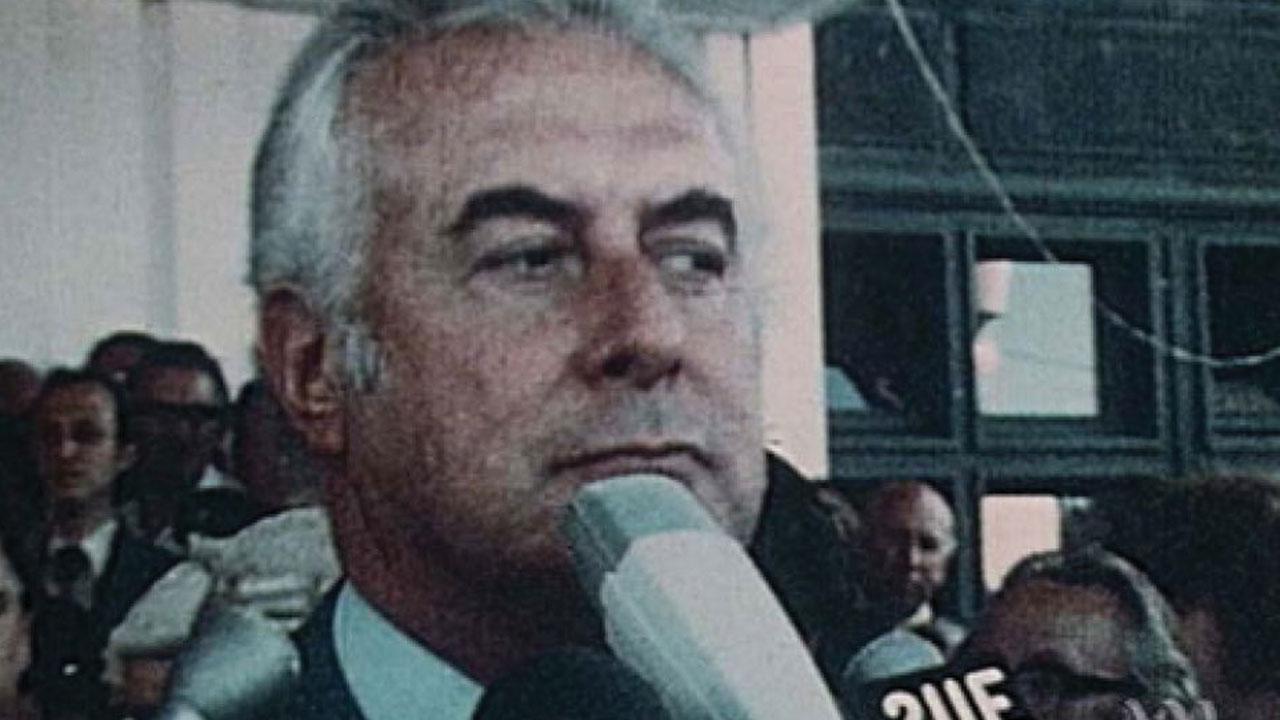

Gough Whitlam’s famous public appearance on the steps of Parliament House.

How TV news worked then

Imagine how The Dismissal might be covered now: live transmission on multiple channels, hundreds of mobile phone videos and instant circulation on social media.

Things couldn’t have been more different in 1975, though. Then, there were four television bureaus (the ABC and the three commercial networks) covering federal parliament.

Australian television had, in March 1975, switched to colour. The next breakthrough in newsgathering technology would be video cameras, which promised more flexibility in shooting, editing and transmission. But their phase-in wouldn’t begin for another two years.

In the meantime, news was shot on 16mm film, using reversal rather than negative stock. The reel from the camera was processed and sliced in editing, mostly without a copy being made. Canberra crews had to drive for more than 20 minutes to a lab to meet processing deadlines. Then they would wait, edit the film and transmit it to Sydney or Melbourne.

This was not a system that dealt easily with the unexpected.

Covering The Dismissal

In the early afternoon of November 11, Wilesmith had sent his assistant to the lab with the day’s first pictures – the political leaders and the governor-general, Sir John Kerr, at Remembrance Day commemorations and later shots of the opposition leader, Malcolm Fraser, being jeered outside parliament as news of The Dismissal became public.

It’s likely the other commercial crews were at the lab when Wilesmith made his way to the front of the building where a crowd was building and the governor-general’s official secretary, David Smith, was about to read the proclamation dissolving the parliament.

Wilesmith recalls that Nine Network journalist Peter Harvey was there but not his crew. So, Harvey made sure Wilesmith would get a good shot. Wilesmith said:

Peter Harvey was pushing me up the stairs. He just got behind me and we got to the top, up the stairs.

I think I held the camera in one hand and the microphone in the other and it all just happened. I didn’t [have to] do too much, but just stand there.

Whitlam spoke surrounded by radio reporters’ microphones. According to Wilesmith, the other TV camera, from the ABC, was further back with restricted vision. That film was subsequently lost.

Despite being surrounded by an agitated crowd, Wilesmith had an almost perfect shot, a little below Whitlam, “standing just to the left … and looking straight at him”.

There are press pictures of Whitlam on the Parliament House steps that day in which all four TV news crews can be seen. But one reason we can assume that they were not all there for that famous speech is that only Wilesmith’s film appears in the various networks’ retrospectives. It can be identified by the angle, a pan right at one point and a zoom in towards the end.

Wilesmith can recognise his sequence by the audio. The sound-head on his camera was:

… a bit worn … so the voice wasn’t crystal clear. It was what we call “wowy”. That’s how you can tell.

By mid-afternoon, the number of people on the steps of parliament was growing. The Sydney Morning Herald put the crowd at 3,000 by 4.30pm. The crush of people made it hard to get out of the area and over to the lab and transmission point. Channel Seven political journalist Mike Peterson said he just “hailed the first car coming through”. He explained to the driver:

Whitlam has been dismissed. [We] need to get this film to [the lab].

Bob Wilesmith, interviewed in 2014, on his memories of The Dismissal.

Recognising TV journalism

People who shoot television news are generally not credited unless they win an award. In the 1970s, the Thorn Awards recognised excellence in television news and current affairs reporting. Channel Seven’s federal parliamentary bureau were runners-up in 1976 for their reporting of The Dismissal.

The main award for that year was given for coverage of events about a month earlier: the killing of five journalists by Indonesian special forces in Balibo, East Timor.

Australia’s premier awards for journalism, the Walkleys, didn’t embrace television news or current affairs until 1978. It was another year after that before they recognised television camerawork.

The first television reporter to win a Walkley was Seven’s Mike Peterson, for a report on finding Kerr, then trying to avoid the public gaze, in England. The cameraman for that story? Bob Wilesmith.

The author spoke to Bob Wilesmith and Mike Peterson by phone for this article on November 3 and November 6, 2015, respectively.

Barbara Alysen, Adjunct Fellow, Western Sydney University

Barbara Alysen, Adjunct Fellow, Western Sydney University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.